Last post: My Story: Next One

How would you feel if someone organised an international awareness campaign against our horrible, demeaning, unhealthy habit of drinking alcohol? Or if an international organisation were to air drop abstinence flyers in city streets at night to combat "unethically high levels of pre-marital sex"? Or if the only way you were to get the potholes and roads in your local community fixed was if you were to comply with your council's "beautification protocol" that involved ensuring your lawn was picture perfect?

I'm guessing you'd be pretty pissed off. Maybe willing to organise or participate in campaigns and protests. Definitely unwilling to buckle to their pressure.

Well, that blatant disregard for the community and cultures often happens when we, our governments and the charities we give to, give aid.

I mean air-dropping wheat seed and harvest to a community

that only knows how to cook and farm cassava, sending in hygiene pamphlets

printed in English to a predominantly Hindi speaking slum and imposing military

forces to restrict entire Indigenous communities to combat moderately high rates of alcoholism

would be akin to summarily giving smokers bags of chemotherapy.

Sure it may end up helping a good few of them in the long run... but in the end you'd be wasting most of your money...

and chances are... they'll probably end up throwing the chemo out and smoking

more in contempt.

Well, those examples are all real.

But when it comes to giving aid, these sorts of ideas, this disregard and lack of consultation with the nations and communities we're working with are too often the norm.

And it's not just the issue of "resistance" or this "grudging acceptance" of aid that's going on... it's wasting billions of dollars too. Billions that could have been spent improving and saving people's lives.

I mean companies conduct huge amounts of research, often

hundreds of surveys and sample testing before even start to develop a new product, yet alone launching it. So why

don't we do that, with the same amount of detail, when it comes to giving aid?

When we talk about giving aid and delivering charity, we not only have to think deeply, and strategically about how we're going about it (I talked about how we need to, and how we can do that here), we also need to think about, and consider the communities we're trying to help. We need to both understand their cultures, their needs, and, just as importantly, their wants, and directly involve them when we direct resources to helping them. So that our efforts aren't wasted, and so as many people as possible can be helped. This idea was another recurring theme in the AMSA Global Health Conference, 2014, and many of the very successful aid organisations presenting at the conference, indeed, many of the most effective aid/charity organisations in the world ensure that they do exactly that; think deeply about and involve the people they're trying to help in their programs. Examples of these, and lessons we can learn from them, I'll give below.

But, as I was reminded by Professor Nicodemus Tedla, a Trauma surgeon, Harvard Fellow and consultant to many aid organisations (amongst many other things) at the UNSW Medical Students Aid Program global health short course last week, we also need to consider the motivations of those giving. He believes, rightly, in many, indeed, most cases, that aid is not given out of goodness, but rather principally with the interests of the donor in mind. The recipient's interests come second.

When we see government assistance packages around the world putting conditions on aid that benefit the donors, through horribly expensive aid-in-kind programs, which involve the receiving nations receiving products sourced from the donor nation (which stimulates the donor's economy) rather than using the most cost efficient resources, when we see nations using aid as bargaining chips, by, for example, withholding aid until demands are met, trade treaties are signed, and when we see aid money thrown at more newsworthy, "positive branding" issues such as HIV/AIDS in Sri Lanka rather than the most needy ones, which is malaria/dengue fever in that region, it's hard to dispute that fact. Even Non Government Organisations are affected thus, as they're held accountable to major and minor contributors and need to make market themselves on successes; hard to do when donors can't relate to causes. Receiving nations have no power or say in this, as those that demand rather than acquiesce, those that have track records of not complying with donors requests don't get developmental aid in the first place. So they're take whatever they can get.

When we see government assistance packages around the world putting conditions on aid that benefit the donors, through horribly expensive aid-in-kind programs, which involve the receiving nations receiving products sourced from the donor nation (which stimulates the donor's economy) rather than using the most cost efficient resources, when we see nations using aid as bargaining chips, by, for example, withholding aid until demands are met, trade treaties are signed, and when we see aid money thrown at more newsworthy, "positive branding" issues such as HIV/AIDS in Sri Lanka rather than the most needy ones, which is malaria/dengue fever in that region, it's hard to dispute that fact. Even Non Government Organisations are affected thus, as they're held accountable to major and minor contributors and need to make market themselves on successes; hard to do when donors can't relate to causes. Receiving nations have no power or say in this, as those that demand rather than acquiesce, those that have track records of not complying with donors requests don't get developmental aid in the first place. So they're take whatever they can get.

This isn't to say all governments and aid organisations prioritize their interests over those they're helping. But it's important to acknowledge that that lack of power or leverage by the recipients of aid is why aid and charity programs tend to be paternalistic and didactic in nature.

So the question now becomes, how do we get around this? How do we ensure that aid recipients, on national and community levels have their actual, most crucial needs and wants met through aid programs? Well, we can emphasise and place importance on the idea of effectiveness when giving, and try and get the most out of our current programs by thinking deeply and strategically about the way we're giving them. Something I talked about in this previous post. We can emphasise the effectiveness and importance of programs that DO consider those we're giving to by highlighting the successes of programs that do so, which I'll do in section 1 of this post.

And we can make it clear in the first place what these nations want, by providing them a platform to do that to, and in doing so providing clarity to donors, and perhaps even placing power in the RECIPIENTS hands in this agreement. This platform can also be a place where aid programs and charities can be evaluated, in one shared space, and successful models of aid delivery can be determined; which I'll talk about in section 2 of this post (click to go to either of them)

But in the end, we can do all this, as nations, charities/NGOs and people by doing the simple thing. Putting our shoes in their feet and understanding them and their needs - by Actually Asking Them.

But in the end, we can do all this, as nations, charities/NGOs and people by doing the simple thing. Putting our shoes in their feet and understanding them and their needs - by Actually Asking Them.

Section 1: Examples and the Underlying Principles of Effective Aid Programs:

Dr Jennifer Dawson

Clinical Psychologist

Founder of Traumaid International

Dr Jennifer Dawson

Founder of Traumaid International

I've talked about Dr Dawson's work before on this blog, in

great detail too (this was a paper I wrote on child abuse inspired by her work)

but what she emphasized the most during the AMSA conference was the system in which she approached

delivering her trauma care.

And that system was one which worked directly with the

community affected.

In the war torn regions in which she works, that is vital,

as with huge amounts of nations' and communities' entire social order

disrupted; sometimes for generations, with low numbers of people fully

developed psychologically (which compromises their ability to pass on care and

function) and with imminent stressors of physical and mental trauma present at every

corner, every effort directed toward helping

them needs to work most effectively.

Providing one-to-one psychosocial and trauma counselling,

with highly trained providers and high-tech tools wouldn't be feasible, wouldn't create an impact in

communities with such widespread trauma. We're talking communities where hundreds

of orphans; many of whom who'd been beaten, abused or even forced to watch

on, and even participate in the killing of their family members, living

alongside communities whose entire female (and a significant proportion of the

male population) population had been raped.

She applied her PhD on community based trauma care to

communities in war torn communities in countries like Congo and Palestine. She

attempted to restore community's natural functioning by helping a few, well

adjusted members of the community reach "solidetere"; a state of psychological wellness with attributes of resilience. And then she taught the teachers, soldiers and leaders of

the community, those who were most likely to be in that state and those most likely to be able to lead, to provide, and teach others to provide basic trauma care. Things like removing stressors like

signs of violence so that post traumatic reliving episodes weren't triggered

and picture based books (important in communities that have low levels of literacy) outlining

how to deal with people going through acute episodes of Post Traumatic Stress

Disorder. These teachers and soldiers would then pass this on to the

wider community.

This teach the teacher approach ensured that her efforts

went the furthest and helped the most people.

Alongside restoring their combined psychological

functioning, she attempted to restore the community's economy too. By providing

small scale, microfrinance-style loans requiring no collateral (the poor often

don't have ownership of land or large assets to secure loans) to the population,

she not only allowed individuals to establish businesses, but allowed a

micro-economy, services and a market to be re-established in the community. Traumaid,

the organisation she founded to do this, also provided basic agricultural

training, in traditionally grown and eaten crops; those that grow best in the

regions, to further this.

Cultural restoration is just as important as economic restoration when it comes to restoring social order in disrupted communities. She organised cultural celebration days to

exchange and celebrate the local culture. People could pass on old traditions

forgotten in the turmoil such as local cuisines, whose very knowledge on was

worn away by years of Western food aid, and traditional dances and dress

making. For children, she organised sporting competitions between schools and

sports days, only possible through the donation of old sports uniforms and

equipment from people around the world. She encouraged the cultivation of local

staples so they could be bought from markets in order for traditional dishes to

be cooked on a regular basis. And of course, restoring this, along with some

semblance of economic security, allowed for the traditional heirachy, of men,

and adults providing for their children rather than the other way around

(handouts are often targeted to children, skewing the normal order of the

community) to be restored.

One example of an amazing project Dr Dawson has worked on through the community.

The results were outstanding, her impact, huge, as a professor from Harvard, who came to evaluate her organisation, suggests. And hearing her talk about the halls packed with male

and female rape victims, the fact that children who'd seen unspeakable horrors

were now able to play and compete in sports competitions and the tears grown

men shed when they were able to taste their traditional dishes for the first

time in decades was an absolute privilege.

She could only accomplish this by working WITH the community

and WITHIN it. With their consent, and with their direct involvement. As touching on these sensitive subjects, being allowed to work in a very unstable, untrusting context, and, most importantly, being able to connect with those she was helping, requires the community to be involved. She worked on the bottom of the pyramid, at the

And her work has been extremely effective. Because it takes

away the foreign invasion feel of aid and because it's focussed on

strengthening the community in a sustainable fashion, from the bottom up, the

communities she's worked in are thriving today. She monitored them over the

long term and ensured the things she set in place were still working, unlike many

conflict and disaster recovery organisations, so the effort went to restoring

the community has paid off.

Unfortunately, Traumaid International had to shut down as it

was unfeasible to go on, so the projects and communities she's restored in 5

different countries are looking like they're the last communities to get help

from her through that organisation (don't worry, she's still monitoring them

remotely and by flying over), but I've talked to her about it and she's looking

to restart Traumaid under a new, social enterprise model, so look out for that.

Her aid delivery model is highly replicable and, as you may have seen in the

last post on these conferences (specifically on this Ted Talk where I got this

quote from), I believe "taking the need for an individual out of the

system" is what allows a specific intervention to be scaleable, and spread.

This bottom of the pyramid approach seems impossible for larger organisations and programs to do. But the methodology, as I've highlighted above, are very scaleable. Many larger organisations can and should learn from smaller ones and take messages they learn to heart, where possible. I've suggested to larger Aid organisations such as Oxfam,

WorldVision and the Australian Foreign Trade and Aid Department that they

invest in conducting some research on the effectiveness of not only their aid

programs, but also that of other smaller ones (and there are many - 56,000 in

Australia alone and 1.2million worldwide) who show promise and have great rates

of success to see if their ideas can be upscaled and used to help more people

through their larger funding, and infrastructural platforms. Her

organisation is one of potentially hundreds of charities who may have novel,

highly effective ideas that have the potential to help save and better millions

of lives.

This innovative and disruptive thinking, especially in the

technology sector, is transforming the very structure of corporations and

economies worldwide, why can't it also change the way charities operate for the

better too? Indeed, former President of Medicans Sans Fronteirs (Doctors

without Borders, one of the world's largest charities) thinks so, as I outlined here.

A cool update from her work in restoring a school in Northern Uganda

But I guess it would be easier if there was either studies and research done, and centralised in one location, for organisations to learn from, or if there was a place where aid organisations could share knowledge and describe reflections so that others could learn from them. Both ideas I'll discuss in the next section. But for now, here's more lessons from organisations which have also taken the needs of the community to heart and has shown great success in doing so.

Social Enterprises

Social Enterprises

These 2 organisations also inserted themselves into the community and learned from them, and in doing so, improved their efficiency, which translates, in this sector, to more lives changed.

Social enterprises are essentially charities designed as businesses. The actual definition of it could be applied in many ways, and I'll talk about them more in detail in the next post of this series. But essentially the basic model is simple, yet exciting. It provides a product of service to people, and sends a large part of the profits to charity. People get the stuff they need while also getting the satisfaction of helping others. It's a win-win.

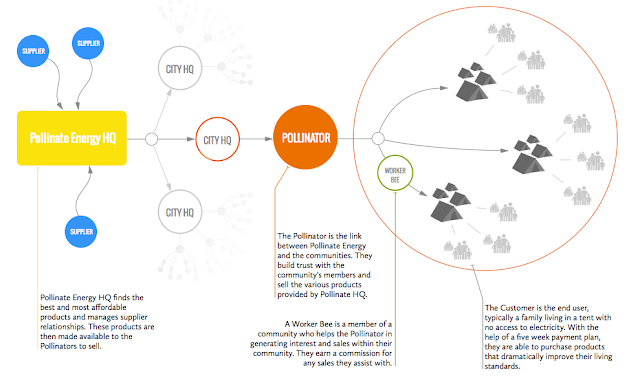

Pollinate Energy

Pollinate Energy provides solar powered lights that double as stoves to slum dwellers in India. Kerosine lamps are the major source of light/heat for some of the world's poorest people, and they're dangerous. The fumes from them are toxic, they are highly flammable, they cost quite a lot to refuel, and in the context of a densely populated, primarily flammable/low-quality material based, enclosed housed slum, they're dangerous. A solar lamp, costing roughly $AU40, can provide a family with much healthier, safer, reliable, free source of light and heat that pays off eventually in the amount saved on fuel. Kerosene itself costs a few dollars a week to maintain. They've estimated lamp buyers save $86 on fuel each year, meaning those lamps pay themselves off in as little as 6 months.

In deciding how to deliver these lamps to the poor, Pollinate Energy had a choice. They could simply buy a load of these lamps, through what they could raise, and throw them at people in slums, hoping they knew how to use them. Or they could create a system that could sustain itself, and, indeed, create some profits. So that it would grow, and so that more and more people could gain access to their revolutionary product.

Their system basically works like this. They sell lamps, and now electric ovens to slum dwellers, on loan style plans. From the reasonable, not excessive profits they make, they invest in creating more lamps and keep expanding themselves there. The most ingenious thing about their plan is how they sell their products. They employ people from within the slums, rather than putting up stands around or inside them, to go through and market directly to slum dwellers. These "pollinators" know the slums. They know who would benefit most from a lamp/oven, who'd need them, how to sell the product, because they could understand them and could provide services like education on how to use the products, maintenance and even collect data, and provide insights that could allow Pollinate Energy to understand those they were helping, and ensure their aid was going where it was needed. And they also involve others in microcosms (slums like Dhaka can have populations over 20million, so this is necessary) within slum regions and give more slum dwellers an income source.

Pollinate not only employed people in regions with almost universal unemployment, they utilised them in the most efficient, innovative manner. With the insights they've gained from directly asking people on the ground, they've improved their operations significantly. And the most touching of the insights was that, contrary to our preconceptions, most lamp owners felt that the best thing about the lamp was the fact that it allowed them to spend more quality family time together, not the the improvements to education (by granting the ability to study at night) the money saved, the quality of lighting or the practical impacts of aid we assume they want most. We tend to look at only the needs of the poor. And though that is necessary, though it leads to us directing our aid to the most dire needs if we think that way, we should never forget that these are people we're helping. Living breathing people, families, no different to yours or mine and just like you and me, they mourn when they lose them. People tend to forget that sometimes...

Pollinate also has other revenue streams along with this. Indeed their major streams work like most social enterprises. They raise revenue in developed countries through products and services and direct profits back to its charitable activities. What do they sell? Well, one exciting one is energy, light for light you could say. A renewable energy company has partnered up with them and offers to donate $100 for everyone who switches their energy provider through this site. It's already available in New South Wales and Victoria, Australia, but may be expanding further to other companies too. You can compare your bills and see if you can save, AND help people AND help the environment (it's 100% renewable!) so why not do it? They also LITERALLY provide a light for light service. You can get a light now for $80, twice the price to provide one, and one will be provided to a slum dweller in the cities they operate in right now (they've expanded since I last talked about them. They're in 3 cities now! The power of their model).

We found out at the Global Health Conference that a major way their partners on the ground ensure the condoms reach, and are used by the most people possible, is through the hiring of a passionate, local researcher to direct their efforts on the ground, and extensive reviewing of their delivery process.

Health Habitat

These 2 are but only a few examples of exemplary programs that have extraordinary impact through working through communities. The Australians for Native Title and Reconciliation council put together this publication, a collection of success stories in Indigenous health to try and highlight the effectiveness of community driven interventions. Many of these stories are plagued with funding issues, despite their remarkable success however. Such programs need to be funded further, and, more importantly, upscaled and applied more widely through federal and state level policies.

A criticism of bottom-up, community based programs is that they cannot be applied in large places, but many lessons learned from them can be taken to other areas with similar traits. These lessons aren't being learned though, and we continually reinvent the wheel and fail when it comes to indigenous policy and affairs. Though the government is trying to learn, they continue to ignore the lessons they themselves tell them when it comes to creating Aboriginal programs and policy. If they were to enshrine some aspect of community engagement in policy, or better yet, acknowledge Aborigines and sign a legally binding treaty, as ALL other nations who have conquered indigenous people have done, Aborigines would be able to self-determine their own programs, which leads to us closing the shocking gap faster and for less money too.

Australia has however shown good collaboration in its aid budget however. Our foreign aid program with most nations we partner with involve some level, and in many instances, high levels of collaboration with local scientists and researchers. For instance, we collaborate well with Indonesia in many projects, and foster interaction between the two nations through education too. I wrote about our collaboration in agricultural research recently too (the essay it was for won the competition actually! I'm headed off to the International Youth Agricultural Summit later this year for it) and though we can improve many aspects of it, it's encouraging to see at least some involvement with the recipients when it comes to foreign aid.

But that's the issue with most foreign aid. Too often it's given in a manner that benefits the donor the most. It's used as a bargaining chip. As I explained above, aid recipients have little power in this struggle. So how do we give them that power? How do we try and encourage charities and governments to learn from the successes of policies that work and INCLUDE recipient nations and communities in the process of aid planning and delivery? This next, I promise, shorter section, will outline my suggestions of how to get this done.

Of course this is assuming many things.

That this data and these methods can be collaborated and still be analysed easily. Good design of the database, perhaps a discussion and upvoting system, would avoid the need for big data analytics tools, but even then, they may be required. Consultancy firms, analysts and researchers can get in on this to find answers. Indeed, if such a platform were to be created, then charities would be more willing and able to work with each-other, perhaps in Consortias, similar to pharmaceuticals and medical research, to help eachother out and ultimately make the sector more efficient.

Even that assumes many things. That charities will be willing to work with eachother. With various benefactors behind each, and different focuses and goals, there may be a lack of willingness to collaborate and focus on one shared target. But government assistance collaboration occurs between many OECD/aid giving nations, and if pharmaceutical companies of all industries can work together to create mutually benefiting goals, then why can't charities?

It also assumes individual charities will be willing to change their models to conform to more effective fields. This brilliant article outlines the sad fact that many don't take up research quickly, or ever at all, for many reasons. Perhaps, in addition to all the ones discussed there, the need to keep a reliable donor base is amongst them.

But the other assumption we're making is that governments and aid programs will wanna give based on the recipients immediate needs rather than follow their own agendas. They may just ignore the recommendations/most effective methods and go down their own paths... But perhaps this next concept/idea behind this platform can change that...

This is positive, rather than negative pressure, and it's something that can convince, rather than coerce (and possibly scare away) potential donors to follow the recipients recommendations for what they need rather than impose their own paternalistic aid on them. Indeed, by providing incentives, and showcasing what projects are happening to improve that nation, recipients can attract private investors, or encourage the wider public to invest in their ideas and nation. If, say, a nation were to offer the opportunity for a foreign or local corporation/company to build powerlines for a generator, with the concession that they establish them in poorer areas of the city and provide connections to 250,000 previously unconnected rural people too, and given, say, a 25 year lease and 100% of income for doing that (the same could apply for road, construction; any necessary infrastructure really), then private companies and foreign governments would be competing for such an opportunity rather than palming it off as someone else's responsibility as they currently are doing. The numbers may not be right or add up right now, but hey, the idea behind that may be valid. And if there was a way for potential investors to see that the country was showing promise and looking to improve through the data displayed in this one central platform, then they'd definitely be more interested.

Who will run it? Perhaps the World Bank. Or the UN. With a big idea I hope to start up very soon that rewards businesses and consumers directly for giving to charity, creating a new stream/channel for charities to raise revenues, I may well be able to establish it myself. An organisation outside the political domain must do it, that's for certain.

Pollinate also has other revenue streams along with this. Indeed their major streams work like most social enterprises. They raise revenue in developed countries through products and services and direct profits back to its charitable activities. What do they sell? Well, one exciting one is energy, light for light you could say. A renewable energy company has partnered up with them and offers to donate $100 for everyone who switches their energy provider through this site. It's already available in New South Wales and Victoria, Australia, but may be expanding further to other companies too. You can compare your bills and see if you can save, AND help people AND help the environment (it's 100% renewable!) so why not do it? They also LITERALLY provide a light for light service. You can get a light now for $80, twice the price to provide one, and one will be provided to a slum dweller in the cities they operate in right now (they've expanded since I last talked about them. They're in 3 cities now! The power of their model).

as of March 2015

Hero Condoms

Hero condoms is another social enterprise that's improved their output on the ground significantly by catering to the people they're trying to help. They operate mainly in Botswana, a nation whose HIV infection rates are staggeringly high - NEARLY 1/4 PEOPLE HAVE IT. They operate on a one-for-one model out of Australia (I'll let you know if there's a similar one here for my American/UK readers), meaning for each condom you, the consumer, buy, one is sent to, in this case Botswana. These one for one models have been criticized for their taking away money from local areas, and creating dependency, but in fields such as HIV/AIDS, or manufacturing of items such as glasses, which don't have a local industry present (in smaller nations) yet have a high need for them, this really works. Condoms are the most effective way to stop not only HIV/AIDS, but any STI. You're literally saving lives by having sex! (How's that for a pickup line...) And every dollar raised beyond that goes to provide mothers with HIV antiretroviral therapy, the best and only way to stop a HIV infected mother from passing on the virus to her children.We found out at the Global Health Conference that a major way their partners on the ground ensure the condoms reach, and are used by the most people possible, is through the hiring of a passionate, local researcher to direct their efforts on the ground, and extensive reviewing of their delivery process.

Detailed and consultative design procedures such as these, with ample follow up and education attached ensures that the people of Botswana who get these free condoms actually use them. One example of a simple design change they implemented that significantly increased condom usage was to change the colour of the condoms from a pale white to clear... As you can imagine... the aesthetic appeal of the white condom was not too high to an African market... And some innovation in their distribution techniques, spreading, and educating people at concerts; where young people, those at highest risk of contracting HIV, tended to congregate, along with schools.

One other way they, and other charities, could improve compliance with aid programs ranging from condoms to water filters is to charge a fee, even a very nominal one, for them. It may seem counter-intuitive that you do so for such vital needs, but charging for items DOES lead to increased usage of products, including mosquito nets, likely because people (a) feel like they bought it, usually meaning they understand why it's useful and therefore should use it and (b) the act of purchasing it makes them feel like a "responsible consumer" rather than a "needy beneficiary", and hence more dignified. Not to mention, it adds sustainability and creates, possibly, a for-profit system similar to Pollinate Energy and microfranchises that allow for the services they're providing to grow. I guess it could be argued that cost would turn away consumers, but the fee could be nominal, and there can still be free ones given out to those who need them. A different model, one that requires deeper thinking and may end up not being feasible or effective, but a possibility nonetheless.

A hilarious Hero Condom Ad. You can order some here: http://www.herocondoms.com.au/shop/

Social enterprises and private NGOs such as these have realised the need to interact with communities to both learn, and be able to deliver optimal results. Not all organisations do so, and they need to take leaves out of the pages of those who are benefiting from it. The development sector is often thus. In section 2 I'll discuss ways we can ensure that we learn from those mistakes. But before that, another aspect of understanding the impact of CULTURE on aid delivery, needs to be addressed.

The Importance of Understanding/Working With CULTURES to Create Change:

Communities are different. Africa is a vast continent filled with billions of people, thousands of languages, multitudes of religions and great economic and cultural diversity. Yet why do we treat it as a country? No I mean we LITERALLY think it's a country.

Even reputable sources, like Time Magazine and The Economist totalitize Africa, lumping all its parts into one, something Africans both laugh, and despair at.

Understanding cultures is essential to making operations on the ground most efficient. Cultural perceptions and taboo can make or break aid organisations and they dictate how communities react and take up aid services. The examples I brought up earlier, of food aid sending wheat and rice to communities which aren't familiar with it, and delivering hygeine education to slum populations in different cities with pamphlets written in the same language, assuming that (a) both cities spoke and used the same language and (b) that the average slum dweller who saw them could read them.

Cultural perceptions and taboos can influence how the wider community will react and uptake services. And they aren't only important to understand when thinking about global health, as cultural perceptions impacts the opportunities and lives of every person in the world.

And one perfect example of this that would make even some of us cringe and unwilling to use services is the re-use of sewerage. The reluctance to drinking recycled water for instance, exists all over the world, and educating people, making people comfortable with that idea is a challenge, one that needs to considered before trying to introduce products or services to the community (I discussed this idea more deeply in this post about Bill Gate's pretty cool invention that turns sewerage into electricity, fertiliser and clean drinking water). If faced with a decision to drink perfectly normal looking water that has a chance of holding diarrhoea causing bacteria and drinking water from what used to be someone's poop, which would most people unaware of the risks choose?

Health Habitat

Good Health Starts With A Good Home

Health Habitat, a foundation that works effectively in improving communities' housing, which directly improves health outcomes, through the training and utilisation of the communities' own manpower, also spoke at the Global Health Conference. And it was in one of their innovative ideas they thought would save time and lives for those they were helping, they encountered this poop problem. One of the features of their work in Nepal was to establish a clean, safe toilet block for a set amount of households to use. Waste would be stored in septic tank like pits, creating fertilizer and also, ingeniously, biogas for families to use in the home. Though the latter ideas' principle was good, but in practice they found that no-one was using it. Why? The villagers were disgusted by the idea they were introducing their waste into their foods, and they weren't sure the poop powered gas stoves were safe to use in the home either. After identifying this though, they included, in the villages already serviced and in future project plans a practical education program that involved community members, getting them familiar and comfortable with using the systems. And it worked! Due to the direct, practical involvement of community members.

An ingenious idea is only ingenious if people want to use it.

Professor Frank Brown and Margaret Hellard

Infectious Health Physician, Advisor to Australia's Government and Oxfam; Leading Infectious Disease specialist

Cultural perceptions of different issues also impact our desire to want to fix them, and nowhere is this most true than in the field of sexually (and drug injecting) transmitted diseases. Both these professors put up the same argument that struck home with me. Why don't we treat, and see diseases, like Hepatitis C, HIV/AIDS and gonnorrhea like we do others? The answer? Because they're largely transmitted sexually, or through drug injecting, things people, even developed nations, find taboo.

Why don't we develop or send prophylactic (preventative) medications for diseases ranging from HIV/AIDS to chlammydia? Why isn't there a huge drive to find a vaccine for gonorrhea? In part, it's the cultural perception that preventing these diseases are YOUR responsibility and that it's YOUR fault if you get them that's to blame. To be fair, it could be the fact that condoms are so effective at preventing these (STI based ones that is), the fact that many of these diseases are curable or treatable in the developed world, to whom most drugs are developed for that stops investment or the conscious objections of conservative parties and people who believe it could encouage people to have more sex that are also to blame. But the fact that cultural perceptions has this impact highlights the need to alleviate some of these before trying to help communities.

We have to ask ourselves though. Are they really at fault? For being human? For not having access to condoms? Or for turning to drugs to cope when they've often been through so much trauma in their lives?

An amazing TED talk that challenges the very way we treat drug addicts, both as doctors and as societies. Why do we judge them for turning to drugs to fill in gaps in their lives due to trauma, when we do the same with family, lives and careers? We have no right to judge them in truth. And I'm gonna be talking about that in a blog post soon.

The Menstrual Man,

Who May Have Solved Indian Women's Santiation Problem.

A specific example of cultural taboo causing huge health impacts is apparent in India, where that time of month for women is literally life threatening. Women going through menstruation are seen as "dirty". They're not allowed to eat at dinner tables, be near food and even pray in that (I swear I didn't mean this pun) period, as this lady describes in this Bloomberg article. " And due to that taboo, due to it not being talked about, female sanitation suffers, resulting in huge gynecological problems. Women are forced to use and reuse rags, newspaper sand or cups in place of tampons. And even when given innovative tools from overseas that deal with this issue, the cultural taboo still kept ladies from using it. "It's a thing from hell," said one lady in this Bloomberg Article. "I have to keep it far from the house, where I pray". Over 300million women in india have little or no access to proper female sanitation in India and it's an issue that needs attention.

But this truely inspiring story holds a solution that may change that. One lone farmer gave up everything, his livelihood, his dignity, even his family, after he realised the challenges women in his life had to face every month of their lives. He noticed the price of tampons was excessively high given the cost to produce them, and so he went on and designed, tested (literally, on himself, as, ostracised by his village and his family, and unable to ask women to test them given the taboo nature of these pads, he created his own uterus from goat skin and wore it around) and produced a device that could manufacture these pads cheaply, and be manufactured in villages and urban slums, where people needed them most. He did this all by himself, and you should definitely give his story a read, or watch the documentary. It's amazing.

It's important aid organisations, government and we, people interested in helping others, consider the culture we're working with things BEFORE we try and change people's lives so our efforts don't go to waste. A potent tale emphasising this idea was told to us by Geoff Hazel of Oxfam Australia (at the annual Expanse Conference for Equality and Justice, Sydney) was that of a Christian Missionary aid mission in Nigeria. Young Christians from all over the world were there, on the ground, urging, delivering sermons to female prostitutes working near construction sites to abstain and refrain from this work and instead do something else. They didn't consider the fact that women who had many mouths to feed often had no choice... They didn't realise that one day of work doing that was equal to a weeks pay as a farmer. They didn't take into account their circumstances, nor their ideas and beliefs on this. And though they meant well.. they wasted thousands in the process, and possibly, if they succeeded in converting some people, created starving families in their wake... That same sentiment and imposition of values, when taken to a national level manifests itself as government aid sending and promoting abstinence in their own and other nations through aid, rather than the distribution/education of the importance of condoms, the most effective method of stopping HIV trasmissions. It's EXTREMELY important we don't impose our own culture on others, for we may do them more harm than good.

It's not all bad news though... Many charities DO take all these factors into account, and DO interact with communities, and are stellar examples that encourage others to do the same.

It's not all bad news though... Many charities DO take all these factors into account, and DO interact with communities, and are stellar examples that encourage others to do the same.

But do governments and large charities who deliver more structural change, learn about, and from the communities and groups they're trying to help, and incorporate those lessons into their plans and projects? Does community interaction matter and improve outcomes as drastically as it does for smaller scale issues?

Why EVERY Nation Involved in Global Development Needs To Consider Those They're Helping.

Australia and its relations with its Indigenous Peoples

Paternalism isn't just rife in aid, it's present in social, indeed, overall government policy too. And Australia's Aborigines are a prime example of that. From the not-too-long-ago (1880s-1960s) policy of essentially abducting aboriginal children and putting them in Christina missionaries, institutions and foster care, creating what's known as the highly traumatized Stolen Generations, "for their own good", to the controversial 2007 seizing of lands in the Northern Territory for, apparently, a systemic problem of child sex abuse that produced no evidence or charges of such behavior (but did open up contracts for mining corporations who previously couldn't get Aboriginal communties' approval) , to the recent plan to close down remote indigenous communities as they're a "lifestyle choice", with little in the way of compensation, resettlement plans (past closures of Indgenous communities have just led to homelessness, higher unemployment, and alcoholism, here's a great documentary on the perils of closing down remote communities) or thought of the culture of the people (the Indigenous people are connected to the land), Australia's treatment of its first people has been historically condescending and brash.

In a supposedly developed nation, Aboriginal Ausralians still have high rates of communicable, preventable diseases such as trachoma, scarlet fever and hepatitis C amongst those seen in significantly higher rates in the Indigenous population. The "Gap" between an Aboriginal and non Aboriginal Australian life expectancy is still over 10 years, and the gap in employment, incarceration and education and many other categories is still huge.

But there is hope. In all but that one shocking stat up there, the gap is closing, slowly, but it is closing. And though there are several horrid examples of failures listed above, there are many policies that have resulted in successes. And a common theme among them is that they're often "bottom up" projects working from within the community to create programs that produce remarkable results.

The Mums and Babies Program in Townsville, on the north-east coast of Australia, took into account local research that surveyed Aborigines and Torres Straight Islander mothers seeking to find out why many weren't using hospital services prior to conception. Unwelcoming hospital environments (due to poor treatment in the past, many Aborigines are untrusting and hence unwilling to use government services), long queues and the child-unfriendly nature of prenatal clinics. The establishment of a morning expectant and young mothers clinic with transport and family friendly environments led to an increase in prenatal clinic attendance rates, decrease in risk factors for baby development (drugs/alcohol/smoking during pregnancy foremost amongst them), and remarkable increases in babies' health; birth weights increased on average by 170grams and perinatal deaths decreased remarkably from 58 to 22 per 1000 births.

The Healthy Housing Worker Program in Western New South Wales (in the outback, east of the centre of Australia) teaches provides community members with accredited housing training programs in things like plumbing, guttering and roofing, allowing remote and rural communities, the focus of these programs, to maintain themselves, saving the government money, and them, time. The fact that it's their own community members doing the work led to 40-90% increases in reporting rates of housing issues that not only increase quality of life, but also physical health outcomes and home durability.

Health Habitat, a foundation that improves housing, which has been shown to be directly correlated with health outcomes, in Australia and internationally, present what they do and why it works in a cool Ted Talk.

The Case For Governments To Apply, Upscale And Pass

Policies To Allow Community Driven Programs To Flourish

The Case For Governments To Apply, Upscale And Pass

Policies To Allow Community Driven Programs To Flourish

A criticism of bottom-up, community based programs is that they cannot be applied in large places, but many lessons learned from them can be taken to other areas with similar traits. These lessons aren't being learned though, and we continually reinvent the wheel and fail when it comes to indigenous policy and affairs. Though the government is trying to learn, they continue to ignore the lessons they themselves tell them when it comes to creating Aboriginal programs and policy. If they were to enshrine some aspect of community engagement in policy, or better yet, acknowledge Aborigines and sign a legally binding treaty, as ALL other nations who have conquered indigenous people have done, Aborigines would be able to self-determine their own programs, which leads to us closing the shocking gap faster and for less money too.

Australia has however shown good collaboration in its aid budget however. Our foreign aid program with most nations we partner with involve some level, and in many instances, high levels of collaboration with local scientists and researchers. For instance, we collaborate well with Indonesia in many projects, and foster interaction between the two nations through education too. I wrote about our collaboration in agricultural research recently too (the essay it was for won the competition actually! I'm headed off to the International Youth Agricultural Summit later this year for it) and though we can improve many aspects of it, it's encouraging to see at least some involvement with the recipients when it comes to foreign aid.

But Aid Isn't Always Given. Or Given For the Right Reasons...

However Australia has recently lowered its foreign aid budget by $1billion, pushing us down to 0.22% of GNI, less than 1/3 of what we should be doing. And there's still the issue I brought up earlier in this piece. We're still the ones dictating aid. And we usually target matters and issues that are of consequence to us. We spend a considerable chunk of our contribution to Indonesia on legal and criminal collaboration, something that needs to be done, yes, but an issue that hardly needs to be lumped in to the label of 'aid'. It's not wrong to benefit ourselves while also strengthening our neighbours, I've made it clear before that it's totally fine, a perfect win-win in fact, to do that. But our commitment has to remain effective. It has to target key issues and infrastructural issues where we can make large impacts. And when cuts come, it can't be down political lines, as it most definitely was in the recent budget cuts.But that's the issue with most foreign aid. Too often it's given in a manner that benefits the donor the most. It's used as a bargaining chip. As I explained above, aid recipients have little power in this struggle. So how do we give them that power? How do we try and encourage charities and governments to learn from the successes of policies that work and INCLUDE recipient nations and communities in the process of aid planning and delivery? This next, I promise, shorter section, will outline my suggestions of how to get this done.

Section 2: Solutions that Help Us LEARN From and Listen to Other Cultures

It's clear from section 1 that the people we're helping, the recipients of aid, need a voice, and need some power to help themselves develop. The paragraph above outlines the fact that Professor Nicodemus Tedla reminded me of; that aid is rarely given without the donor's interest at heart. And that, along with poor forethought and lack of systematic, deep thinking, is something that often reduces the effectiveness of aid and charity. I have an innovative yet simple idea that could potentially change all these issues. But regardless of whether or not that could ever take off, systematic, systems based evaluation is necessary to ensure our efforts to help others goes the furthest.

My Idea. A Place Where People Can Tell Us What They Need.

My solution that promises to give nations and people a voice, is simple, but could be a gamechanger. What if we created a universal platform for developing countries, and developing regions to outline, highlight and dictate their needs, rather than have it dictated to them. This platform is simple. Governments and registered NGOs can put forward and highlight issues in a nation that need resolution, that aid organisations, governments and possibly even private enterprises and investors, can come in and help deliver.

Collecting Data And Finding Problem Points Through This

Of course, first, they need reliable data and methodology to even be able to figure out key issues to solve. Data which many developing nations simply don't have the capability of collecting easily. Innovative, adaptable yet cheap data collection services, like UNICEF's Rapidpro SMS data collection tool, promise to make this data easier to come by. The tool is very cool, and encourages surveyors, whether they be governments or charities or potentially private enterprises to ask simple yes/no / one word questions to people on the ground. Results are collected live, and can be anaylsed to highlight issues or strong points and actions like campaigns can be conducted through it too. The fact that it's so adaptable, and organisations can gain evidence for almost anything for it makes it even more exciting. You can literally engage individual people in improving their own nations/regions/communities through this, and it should be marketed to people on the ground as such, if and where possible.

A survey feature of RapidPro outlined.

Larger surveys, even censuses can be collected in a much cheaper manner too, through using cheap technology, rather than cost and labour intensive papers and cost intensive breaking edge tech, which I talked about previously here. You can watch a great Ted Talk outlining this idea here.

NGOs, Aid organisations and private enterprises can contribute to this data with any they had gained themselves, and though data quality may be an issue here, if general trends and general problem areas can be identified, then that's enough to formulate ideas and solutions from. Even when data can't be attained, groups can highlight crises, disasters, areas with particular shortages or deprivations, and general issues they'd like to see fixed on there.

Observations (not strictly data) and discussion of issues will also be accepted and documented. And this can also serve as a place for towns/communities to "complain" about shortages which may be able to be filled by charities or aid programs to epitomise, refine and potentially even transform the ways in which aid is delivered.

The major problems/issues found will be grouped together, with general trends and issues highlighted, separated in terms of their nature/"sector" of development (ie - water, sanitation, agriculture, infectious disease, urbanisation, child labour) so that aid organisations and programs can add themselves in, ranked in order of urgency/need at every level necessary; that is, on an individual community, town, state/province, national and regional level.

Now Problems Are Identified, Possible Solutions Can Be Developed/Outlined and Potential Providers of Solutions for These Can Fall Into Place

Through this solid, standardised platform, charities, aid programs and governments can reduce wastage and duplication of research, identify areas short on research, and then ultimately deliver services/products to regions that need it most, or that can reach the most people.

Similarly to the problems, this platform can be a place where the nature/model/delivery of solutions can be discussed, evaluated, through qualitative and quantitative data, and be made more efficient.

Much research and much observation is being done by many individual organisations/parties to ensure that the money and resources we direct to aid go on to help the most people and cause the biggest impact. But a lot of this research is, again, like the issues, duplicated, many of the ingenious ideas and models of delivery lost amidst the vast array of methodologies and data out there. Global Development is a developing sector, and it's horribly inefficient when compared to the business world. The money-tight nature of the "industry" and often the lack of talent and knowledge by charities may be to blame for this, but this platform can change that.

Individual charities are being evaluated for their effectiveness, for how much good they do per dollar spent, more and more, with Charity Navigator and GiveWell being the 2 most famous, reliable ones. It's great that this is happening in a field which is only developing itself, as it guides donators to programs that will help the most people. But what ISN'T looked at enough is what methods, products, procedures or models of delivering aid outcomes are most effective. Is condom dispersal or providing antiretroviral treatment to HIV infected mothers (so they don't pass it on to their children) more effective? Is establishing/upgrading a school or paying for a child's school fees more effective or viable than radio broadcasted education programs? Would using a microfranchise model be more effective in providing home electricity than building and investing in a reliable generator and an upgrade in power lines? Would building sewerage pipes/lines for an entire community be more effective than teaching and providing families with handwashing training/materials? Would those answers for all these be the same in Nigeria and India?

Through this platform, data accumulates in 1 place rather than many. And various models can be outlined and compared more efficiently than ever.

Through this platform, data accumulates in 1 place rather than many. And various models can be outlined and compared more efficiently than ever.

If large water access organisations were to have an outline of the most effective products, methodologies and models to dig wells; let's say this is that most effective model (taken from the Village Drill) that an organisation should use mini/man-powered, compact well drills, dispersed through communities with trained locals guiding and using a communities' own labour force to drill the wells to ensure many villages end up having a well dug in a faster times, then more people would have access to clean water as water programs start following suit. From there, Water Filter providers could present themselves and distribute filters to communities that have been confirmed as having a well dug on the database, rather than having to invest in research to find deprived areas themselves, and microfinance bank partners on the ground can approach communities and offer them financing to pay for this shared community filter. Once a region has been marked as having clean, safe, drinking water, medicine providing organisations can focus on other regions when it comes to dispersing water borne illnesses such as cholera as the root cause of these diseases, contaminated water, has been taken out of the equation. Multiple sectors combine to deliver one outcome. All through one platform.

That this data and these methods can be collaborated and still be analysed easily. Good design of the database, perhaps a discussion and upvoting system, would avoid the need for big data analytics tools, but even then, they may be required. Consultancy firms, analysts and researchers can get in on this to find answers. Indeed, if such a platform were to be created, then charities would be more willing and able to work with each-other, perhaps in Consortias, similar to pharmaceuticals and medical research, to help eachother out and ultimately make the sector more efficient.

Even that assumes many things. That charities will be willing to work with eachother. With various benefactors behind each, and different focuses and goals, there may be a lack of willingness to collaborate and focus on one shared target. But government assistance collaboration occurs between many OECD/aid giving nations, and if pharmaceutical companies of all industries can work together to create mutually benefiting goals, then why can't charities?

It also assumes individual charities will be willing to change their models to conform to more effective fields. This brilliant article outlines the sad fact that many don't take up research quickly, or ever at all, for many reasons. Perhaps, in addition to all the ones discussed there, the need to keep a reliable donor base is amongst them.

But the other assumption we're making is that governments and aid programs will wanna give based on the recipients immediate needs rather than follow their own agendas. They may just ignore the recommendations/most effective methods and go down their own paths... But perhaps this next concept/idea behind this platform can change that...

By Saying What They Want, Recipient Nations Not Only Outline Their Needs, But Can Offer Incentives to Those Fulfilling Them

Many nations and aid organisations will follow any recommendations made by this platform, because many do simply wanna do good without looking for rewards. But for those who don't, or for those looking for more incentive to give more, recipient nations will have something to bring to the table. Something that can not only outline what they need, but also outline what benefits those who invest in their betterment can get for them.This is positive, rather than negative pressure, and it's something that can convince, rather than coerce (and possibly scare away) potential donors to follow the recipients recommendations for what they need rather than impose their own paternalistic aid on them. Indeed, by providing incentives, and showcasing what projects are happening to improve that nation, recipients can attract private investors, or encourage the wider public to invest in their ideas and nation. If, say, a nation were to offer the opportunity for a foreign or local corporation/company to build powerlines for a generator, with the concession that they establish them in poorer areas of the city and provide connections to 250,000 previously unconnected rural people too, and given, say, a 25 year lease and 100% of income for doing that (the same could apply for road, construction; any necessary infrastructure really), then private companies and foreign governments would be competing for such an opportunity rather than palming it off as someone else's responsibility as they currently are doing. The numbers may not be right or add up right now, but hey, the idea behind that may be valid. And if there was a way for potential investors to see that the country was showing promise and looking to improve through the data displayed in this one central platform, then they'd definitely be more interested.

Conclusion

There's much more to think of when it comes to this idea. How it can operate, how it'll be structured, who'll run it. A lot more. But if this were to happen, then the $700 billion a year we currently give to charities/aid, of which a good chunk is developmental aid, will go a LOT further than it currently is. There are many assumptions here too. That governments of recipient nations are competent, un-corrupt and able to maintain these well. It's clear that a few flag-ship, stable, piloting nations will need to be selected to trial this idea before other nations can get on board. That's for sure.Who will run it? Perhaps the World Bank. Or the UN. With a big idea I hope to start up very soon that rewards businesses and consumers directly for giving to charity, creating a new stream/channel for charities to raise revenues, I may well be able to establish it myself. An organisation outside the political domain must do it, that's for certain.

But regardless. This post should hopefully make it clear that it's vital that we listen to those we're giving to, to ensure that our good will goes the furthest.

And you know what... even if you don't care about global health and inequity... You still need to take this message to heart. Because the basic principle emphasised in this - to always ask, involve and consider those you want to help are universal. They can be applied to anything. From social policy and welfare to improving sales in business to even to our everyday social interactions.

We NEED to understand and consider those we're trying to help. Because without doing that, we're not really helping them at all.

We NEED to understand and consider those we're trying to help. Because without doing that, we're not really helping them at all.